The transaction of selling and buying goods is a concept that is drawn from a history that is hundreds of years old. It’s a simple process in many ways which can often be disguised due to the way it’s presented, specifically on a larger, global scale where trading relations creates countless jobs and activity. Expanding economic interaction across countries is often referred to as globalisation, a term which McLaren ,2013, pg. 8 notes as ‘a way to buy and sell goods/services across national borders; for a firm in one country to set up production facilities in another; for an investor to invest in securities originating in another country; and for a worker in one country to travel and seek employment in another’. The complexities surface when political factors such as those formed from immigration policies and tariffs are applied which make the environment more difficult to trade in. This is especially relevant for those countries which are developing, where the GDP and national economy isn’t as strong as those who are willing to trade via their own preferred strategy of comparative advantage[1]. Producing and selling goods in the world economy is therefore as much a political process as it is a financial imperative to survive and grow. Developing suitable strategies which understand competitive relations and power dynamics in the market whilst simultaneously recognising the need to turn over a profit is therefore vital. The marriage of political and economic factors is as much a base of knowledge to be aware of as it is an opportunity to manage the different principles to positive effect.

Managing the different considerations of trading activity in supply chains has been defined and outlined in many ways. Professor of the MIT Sloan School of Management Jay Wright Forrester was a key facilitator in acknowledging management as a holistic discipline, and associated such practices with the term ‘Supply Chain Management’. As early as 1958 Forrester noted, “Management is on the verge of a breakthrough in understanding how industrial company success depends on the interactions between the flows of information, materials, money, manpower and capital equipment… The way these five flow systems interlock to amplify one another and to cause change and fluctuation with form the basis for anticipating the effects of decisions, policies, organisational forms, and investment choices”. Categorical as they may seem, Forrester was able to outline the relation between such variables and demonstrate that interactions have their own momentum and lead to outcomes which vary and fluctuate in their own ways. Mentzer et al, 2001, pg. 18 details that the purposes of such outcomes are to, ‘improve the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole’. Performance in this instance is not just subject to a financial value but also an opportunity to be more involved in the marketplace. Whereby the different processes and activities that produce value for the consumer are more closely scrutinised/analysed (Christopher, 1992). Becoming more involved, stretching capabilities and evolving is as much a philosophy (Cooper and Ellram, 1993) as it is a working practice (Tyndall et al, 1998). Dedication to management can therefore been seen as a mind-set, which is there to be honed by the workforce and for the benefit of the market place.

Performance is also increasingly being linked to sustainable practices, a topic which has been much discussed but left open for further exploration, discussion and action. Often considered a ‘license to do business in the twenty-first century (Carter et al, 2011 p.14)’ sustainability is all about responsibility and information in supply chains being accessible to consumers so that they can decide whether they agree to support the business in practice or decline its marketing appeals. Carter and Rogers use the word ‘transparent’ which is a good way of thinking about it, defining the term as, ‘the strategic, transparent integration and achievement of an organisations, social, environmental, and economic goals in the systemic coordination of key interorganisational business processes for improving the long-term economic performance of the individual company and its supply chains’ (Carter and Rogers, 2008, p. 368). While initially not seen as a measure of financial success (Walley, 1994) it has moved beyond common practices of supply chains and served as an analytical curiosity. Whereby life-cycles of products, the costs of wastage created and the generation of by-products (Linton et al, 2007) can all be viewed as projects to serve environmental concerns. Thus, supporting a culture whereby consumers are informed and respected for their concerns instead of being viewed as passive, routined purchasers.

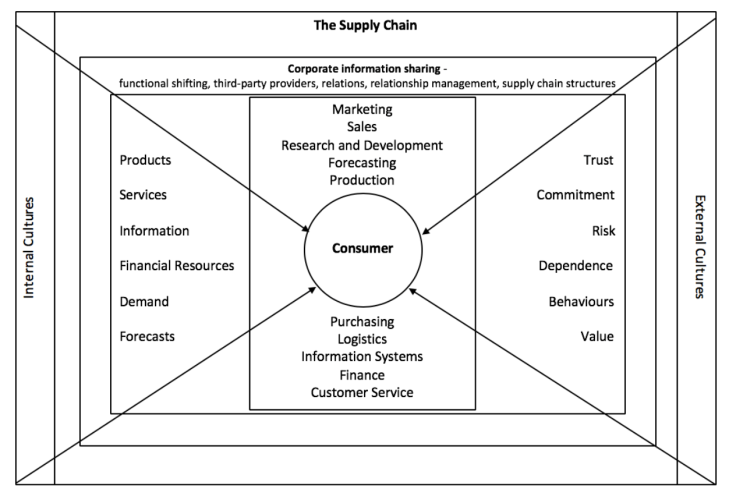

What it interesting about this is how Forrester’s earlier claims of ‘transactions of information (1958)’ have developed from being something internally considered to something which is actively part of consumer behaviour. Managing is therefore not just subject to a series of processes and internal values but also to the image of the industry from the outside. The next steps are therefore to consider each process as a suitable concept for consumers to understand and respect, a management principle which respects a knowledgeable consumer as well as financial value. This pressure is different depending on the culture products are being sold into but the denial of recognising these factors are generally to the detriment of organisations whose management staff are ill-informed to the external rhetoric and cultures. Growing as a community and not just as a business is therefore pivotal for the momentum of Forrester’s earlier claims to truly sink in. Let’s now consider the full scale of this, by adding the model of supply chain management (Mentzer, 2001, p 19) with an outline of ‘intelligent consumerism’.

Consumer focused framework – basic conceptualisation for considering the consumer as someone who is informed, prioritised and considerate to the processes related to product life-cycles. Partially inspired by/developed from Mentzer et al, 2001, pg. 19, Journal of Business Logistics Vol 22, No 2

The consumer focused framework prioritises the consumer themselves, putting them at the centre of the supply chain network. In this instance, the consumer can either be a certain individual or a select group of people; they can be the buyer themselves but more appropriately they are the user whose request for the product is drawn from a set of needs and/or wants. To think of it another way, think of the different elements of the supply chain as the foundations of a property, the internal and external cultures as bricks and the consumer as the cement which holds the different elements together. What is important about this theory is that by putting the consumer at the centre there is a clear determination as to where the focus lies, threading the different elements and processes together to sustain a certain synergy.

What is useful about thinking of the supply chain network as consumer led is that it prioritises sharing knowledge to its consumers in order to be more attractive to them for further purchases. It demands each task to be re-examined, challenged and shared with its audience in order to thrive and create sustainable measures within its business practices. Logically, this is rather a naive and perhaps optimistic theory which is poorly executed as the core principles of the market is always going to be financial (both profitable and/or maintainable in its budget). But the challenges of putting only financial variables at the centre of the framework is that it creates a mentality in which consumers are considered numbers rather than minds who fluctuate in terms of their own thought. Sustaining their working practices to fulfil the demands set by consumers is therefore a much more promising way of determining strategies which strengthen opportunities for growth as it respects the fluctuating psychology and nature of the market.

This idea is not to say that information sharing is whole in terms of it’s transparency. If anything, organisations will determine the information they share with tight regulation and consistent analysis. Progressive practices which help to develop this is not easy, especially when considerations to middle-tier and off-contract suppliers are not always complaint and visible to the practices of the end user. The more successful an organisation is, can therefore be determined by how many changes are made and how accessible they are shown to audiences.

[1]Easiest way to think about comparative advantage is if you consider the power one country may have due to the stronger capabilities and products they have over other countries. Often it’s not just related to the product a country grows/manufactures by themselves but is a product of a series of factors such as physical capital, legal power, labour market, education/strategy, economic climate etc.