“Success would come through a process, an accumulation of tactical actions over time, rather than a single tactical event”.

The quote above is taken from the publication ‘Understanding Land Warfare’ (Tuck, 2014, p. 85). Success from this angle, is derived from the concept of a series of actions which each work together in order to create a certain outcome. The satisfaction of success is therefore not singular but multifaceted – whereby each action, process and movement is designed to be successful in its own right. Multifaceted success is therefore as much a pivotal working mechanism as it is a fulfilment of demands. Or to put it another way, success is as much a process as it is an end result which is sustainable and has the potential to grow if managed correctly.

Whilst this concept of success is derived from ideas surrounding land warfare it is possible to understand the multifaceted angle as something more broader which can relate to social and economic agendas in industries not just related to those of defence. As to be successful is for an organisation to make intelligent decisions, to be curious, make smart investments and build a team who are supported to be strong in their work life. Their strategy for commercial profit is as much about understanding that the ethics and toil which they put into their organisation is of equal importance as the returns they make. Without an understanding of every angle, the ambition to learn and grow has the potential to falter and success to be limited rather than sustainable.

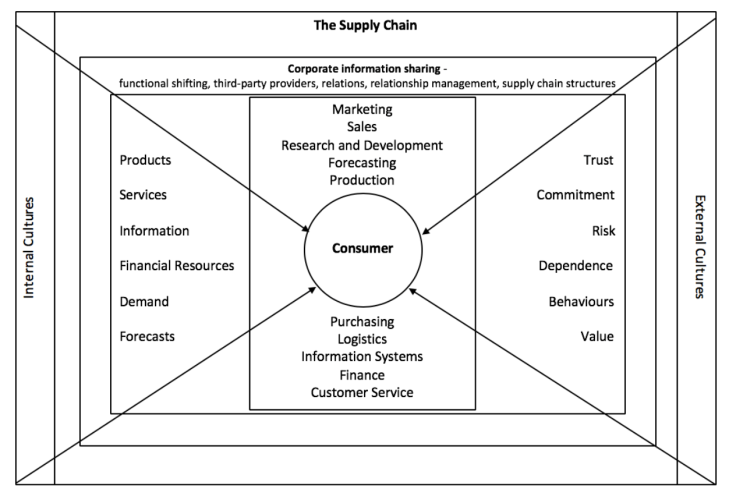

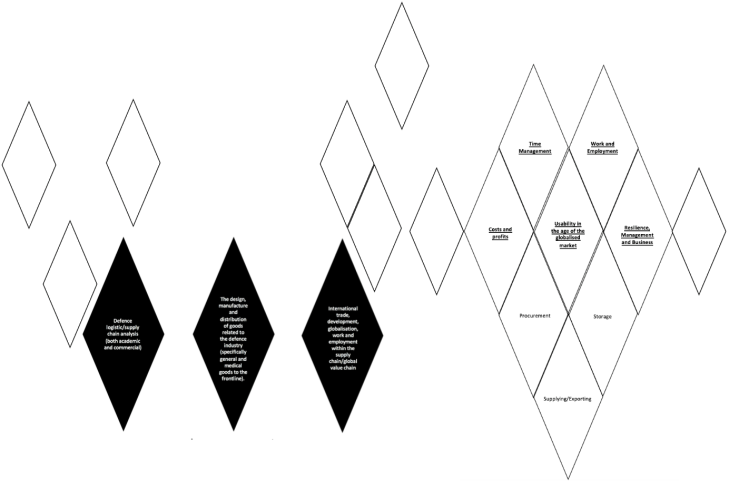

For the purpose of this blog post, supply chain success is intrinsically linked to this multifaceted angle. As without conceptualising the breadth of supply and demand, there is a risk of having a chain of events which aren’t sustainable in the long-term, creating undesired effects within the market. The following part of this post will explore some of the key aspects of sustainable success. Specifically, the frameworks will be broad in their nature as at this time I just want to outline them so that they can be analysed and applied as the blog progresses.

- Time Management

- Work and Employment

- Finance

- Product usability

- International Business and Development

Time Management

I’ve decided to start with time management as it can be a key framework in understanding how supply chains operate in real time. As an example, when dealing with commodities, the life-cycle of a product is determined by a series of factors such as: conception, resourcing, analysis, adaption and integration into the market. All of the variables that are taken into consideration are there to be both profitable and sustainable. Without an understanding of how the different segments work together, there cannot be an understanding that a supply chain is a sum of all its parts (a holistic discipline/process). Meaning that every aspect has to be attended too and given an appropriate amount of time to plan and process – in effect, supporting the requirements needed for supply chain sustainability.

Time management is not only a way to ensure that the effort given is recorded to maintain operations, it also encourages efficient practices which support development opportunities to take place. Managing each activity is a full-time job in and of itself and needed in order to ensure the other variables of the supply chain are well maintained. However, without the capacity to recognise patterns of repetition it becomes difficult to apply changes which encourage strategies of improvement. The question then becomes, why are practices of supply chain operations needing to be progressive if routine and regulations work in terms of being commercially profitable? The answer is two-fold. For one the demands of supply chain activity are based on the demands of the market. If the market is busy, steady or disrupted the operations have to respond competently. Hence, the more thought and discussions that are created, the more opportunity there is in securing suitable answers/resolutions which are helpful. Second, maintaining control of supply chain activity is required in order to have confidence in the actions which are unfolding, but no-one can predict how things will change – meaning that the nature of the market is fluid and serendipitous. Being open to this reality and letting go of some of the control of the philosophy of the tight management practices is therefore pivotal as it helps to spur on attitudes which are considerate and progressive instead of monotonous and complacent in the strategy which is implemented.

When considering time management in supply chain activity, it is important to recognise that ultimately it’s a framework which supports analytical and critical thinking. The success and failures can be lessons as to how best to move forward in order to try and develop supply chain activity even further. Analysis through documenting, fore-casting and communicating findings to one another is an example of how time management frameworks can potentially work in reality. In effect, helping to create changes and decisions which support the organisations ambitions.

Work and Employment

While time management is useful in terms of conceptualising tasks both as individual processes and as a whole, it is of equal importance to consider employees who facilitate such activity. Capabilities such as integrating, analysing and developing supply chain processes cannot be taken for granted; as to not take a workforce seriously is to hinder sustainable and commercial viability.

Within any working environment you’re only ever as good as the team you are surrounded by, and this is ever so critical in supply chains where the holistic nature requires strong communication skills. Relations between suppliers and buyers, co-ordinators and purchasers, service staff and customers all rely on consistent, reliable communication networks. Therefore, taking any member of staff for granted and not listening to the voices from different departments is only going to hinder any possible progress both for the individual themselves, the team and the organisation. Ideally, this should encourage training opportunities for workers to develop their skills in support of the industry they are employed in. However, how this manifests is more tricky to measure as skill development is determined by a series of factors such as personal ambition, funding opportunities, encouragement by management staff, length of employment within the organisation, etc.

Categorising workers and ensuring that they are equally trained is also challenged by the fact that supply chains are not strictly operating under one roof. Whilst buyers may go through a rigorous vetting process in order to ensure the suppliers they set contracts for are following their guidelines, they may find their control to be inadequate. This idea is based on the reality that for suppliers they may choose to use additional workers outside of their company to complete certain tasks (SME’s, home-based workers etc). The potential for workers to ‘get lost’ in the supply chain is a reality when considering the suppliers use of additional/contractors workers. Further attention is therefore required, as without regulatory practices there is a risk of maintaining activities which are unethical and unsuccessful in promoting workers rights. Whilst this is a challenge related to suppliers, it’s also important to consider the internal relations which happen within the company who are buying the goods.

Hierarchical structures might work well in terms of distributing responsibilities but how the leaders at the top communicate to the middle and lower-tier is important to recognise. This is because everybody is essentially working for the same goal: to sustain, develop and profit from the organisation both professionally and financially. Recognising any barriers which hinder successful access/communication across the supply chain network therefore requires further challenging. As if the outcome for workers is financial, why should there be political factors which discourage conversation and access to other employees (specially access to higher level/management staff)? This is something to consider as the blog develops and analyses the relation between workers and supply chain operations.

When considering work and employment the key focus is communication, personal development and access to workers within the supply chain. Each will be considered in later posts, for now the outline of financial factors will be established.

Costs and profits

Imagining the realities of integrating time management frameworks and employment capabilities comes more naturally to me than the financial components embedded within supply chain practices. This is because much of my research and employment has been in relation to operational procedures, whereby finance takes on a role which acts more as an outline rather than something to be analysed vigorously. However, in order to develop my knowledge and try to reach a competent level of exposure to financial elements I’m going to attempt to explore the following throughout this project:

- Product design and commercialisation

- Costs, profits and profit margins

- Financial data collection and analysis

- Risks, successes, failures and sustainability

- Financial cycles and the relation to the supply chain life-cycle

The following is a brief extract and introduction which sets out to explore the relation between supply chains and finance. The hope is that this will act as a foundational understanding for which the subject headings outlined above can be developed from.

“Financial accounting involves the recording, analysis and communication of financial transactions of an organisation to users. In essence, it is about assimilating an organisations financial transactions into financial statements. Financial management on the other hand deals with helping decision makers in making financial decisions about how funds should be raised by a business and then how they should be invested so that the investment increases the wealth of the owners.”- Ansari Irfan, Accounting and finance in defence logistics, Defence Logistics, 267/268

Financial transactions in their simplest form can be identified as expenditures/costs which are made in order to fulfil a certain operation. The costs are typically used through a budgeting plan which is then processed for the purchase of goods or services to take place.

Categorising inventory items into expenditures can be useful when trying to establish cost-effective practices as strategies of inventory management can make suitable decisions whether to keep the items or discard them. This is done by aligning the amount the items are being utilised with the costs it takes to purchase and provide them. Irfan identifies two types of products: current and capital. Current products are consumed within a finite amount of time in order to fulfil a need for example, food, fuel and wages. Capital, on the other hand, are those whose usability extends beyond a certain activity and can be longer lasting such as vehicles and construction goods.

Processing the costs that are related to inventory items usually falls into two different accounting practices – cash based or accrual based accounting. For the former, cash is transferred from the seller to the buyer at one particular point in time. This is a useful technique as it makes it easy to identify specific purchases on financial statements but it also lags behind accrual based accounting as factors such as liabilities aren’t taken into account. Under the accrual scheme, the purchase price of an asset is spread over the time a product provides the benefits that it has promised to the customer/buyer. The pressure to rid any inventory which is idle is therefore more apparent under the accrual accounting method – as otherwise the budget will be weakened by products whose usability and costs aren’t aligned enough to support its purpose as part of the budget.

An effective budget takes into consideration the objectives which it seeks to achieve, plans/organises the way it will meet them and successfully co-ordinates and communicates in a way which understands the disciplines of the organisation. Taking a holistic approach to financial transactions and analysis is therefore suitably fitting to the theme of supply chains – as they both prove to be multifaceted in their agendas and activity. The time it takes to make successful transactions both financial and operational takes this holistic nature into consideration when splitting costs into direct and in-direct costs. Direct costs are associated with the value of the inventory item itself, whereas in-direct costs look at the additional costs that are associated with inventory items such as the storage space the item takes up, the time and labour it takes to look after the item. Statistical analysis which takes into consideration time series, probabilities, what-if scenarios, linear regression and probabilities can all help when trying to distinguish changes in direct and in-direct costs for budgetary planning. This isn’t a definitive way to plan as nothing is ever completely certain but it at least gives an indication as to how to move and adapt inventory items for the purpose of cost effective practices and sustainable supply chain management.

For the purpose of defence logistics, considerations of industrial policies, international alliances and government actions make the budgeting process more of an estimate rather than a significant sum which can be deemed 100% accurate. However, as a financial plan, you can’t dismiss the fact that the budgeting set in place does help to support strategic objectives over a period of time which routinely embed financial elements into their logical thinking pattern.

Usability in the age of the globalised market

The previous sections have outlined some of the key components of supply chain procedures, specifically operational and financial considerations. Whilst it might seem obvious, it is important to bring attention to the eventual user of the product which is been manufactured and sold to them. As the strategies developed to support time management frameworks, employment opportunities and financial sustainability will forever be redundant if the product itself does not have the correct aesthetics and functions.

The manufacture of products increasingly take on diverse and complex procedures, whereby it is common practice for organisations to outsource jobs in order to benefit, financially, from cheap labour. This is both an economic and political move, in which the labour involved in crafting a product has its own geographical terrain. Each stage of the process from conception, production and distribution adds value to the product itself and so the pressure of creating effective products in this exhaustive environment is a consistent priority.

For the purpose of this project, I’m looking at exploring these manufacturing processes for products related to supplies to the frontline – specifically medical and general goods. How these products ensure that the labour involved creates a product which can be effectively used whilst ensuring value added practices are managed and maintained is an investigation that will be pursued. I also want to take into consideration the characteristics of the products themselves, simple bites of information which gives an indication as to how products are designed to work. I feel that a mix between the complexity of procedures and the simplicity of the end result, will help to give a certain clarity to the cycle of the supply chain of the designed goods in question.

Global value chains is an area which I studied as part of a developmental framework at university. The lines between developmental thought and defence operations forms the next part of this section – that is the relation between humanitarian endeavours and practices of NGOs with the organisations of defence and armed conflict. In the publication ‘Defence Logistics’, Peter Antill discusses how the capabilities of military are deployed to ensure relief agencies can work in an environment which is enveloped by devastation that is caused either by natural factors or those that are man-made. Antill further examines how the aims and strategies differ between those formed from humanitarians experiences and those from defence – suggesting that the relation is a juxtaposition that is both complementary and divided in its ambitions and actions. Antills work acts as a strong introduction to the subject and I’m looking to explore how these relations manifest further – something I hope to find through secondary research.

Resilience, Management and Business

Stringing the above subjects wouldn’t be complete without considering how defence logistics manages the information used to create and maintain a successful operation. This brings to light questions such as:

- How is knowledge collected and recognised within the logistics value chain?

- What developments have been made in terms of the ICT platforms which are used?

- How can business trends and a communal focus spur activity into directions which might broaden horizons for logistical operations or limit them?

Ultimately, how to decipher opportunity, prosperity and intelligent thinking is needed for sustainable practices. As mentioned earlier, these sections will be identified and explored further as the blog progresses, but before then I’m going to establish some of the services which supply chains practice which make them important in the trading market including procuring, holding and exporting goods.