Synopsis

The industry of protective apparel reflects upon the human condition by manufacturing garments which take into consideration potential threats. Clothing in this sense is functional, providing a level of support to the human frame through the properties of the garment. Within this project I aim to focus on protective apparel, not as a surface but as a security component . The first section focuses on the historical developments of protective apparel, from early designed armoury to contemporary synthetic materials. In order to rationalise the developments of defence material I aim to analyse particular objects which come to represent a particular era such as Plate Armour, helping to symbolise the different ways defence has been physically realised. The second section focuses on the chemical makeup of Personal Protective Equipment, analysing product descriptions within the current market place. Moving on from this, I aim to explore the relationship the wearer has with the garment, how they move and interact in the environment whilst wearing protective apparel. The function of the garment and the steps made in order to manufacture the product has developed into a billion-dollar industry. By presenting Personal Protective Equipment as something that is still in development, I will reflect on an industry which investigates materials and constantly adapts to the environments condition.

Introduction

When we think of conflict we think of the people, the anger and the devastation it causes. The reflective response is a communal mode of thought and one that is cared for by those who share an interest in it. In this sense, conflict is information, rationalised and responded to without the weight of physically being present in the environment. For those who are present, the action which unfolds is a consequence of a series of operations moving forward. The footsteps are personal and when completed lead to a memory hastened with a physical reminder of what the body feels in a state of tension. What remains important is no matter how much rationalisation and reporting is made, the physical action of being part of an environment of conflict is never understood by the observer, it is only truly felt by those present.

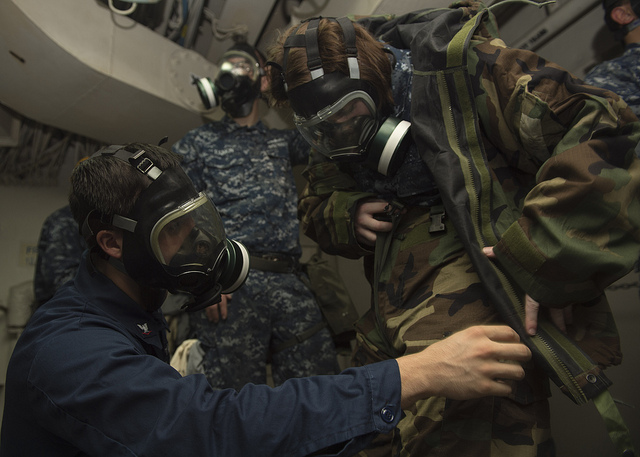

For those unprepared conflict is limited to its resources but for those who inhabit an industry based on responding to it, it is a field of items designed and manufactured to protect when action unfolds. The armed operative wears their defence, using uniform which is engineered to respond to the potential threat. The uniform changes the movements of the armed operative, adding weight to their frame and creating a structure where resources can fit in place with ease.

As a surface armed uniform is symbolic in its presence, presenting a patriotic figure which is political in its nature. The idea of protection is re-enforced by communities who reflect on the uniform, viewing it as either a respected way for pursuing a life of defence, or as a fearful encounter of what may breed confrontation. As an observation, uniform creates a powerful dialogue but for the operator themselves it provides a self-awareness, a physicality which focuses on movement, restraint and continual adjustments.[1]

If the uniform is a reflection upon the behaviour and movement of the soldier, then the designers who produce garments have to represent something which is pragmatic rather than fashionable, functional rather than playful. In this context, the designer isn’t an instrument within the retail market, they are makers who are part of the equation in securing the fighter whilst on duty. Each component, including webbing straps, Modular Load Carrying Equipment and the printed surface of camouflage mould onto the body. By adapting the uniform, the designers are never still, searching and transforming the material in order to maximise the rationalisation of the incoming potential threat.

We can see that by looking at the progression of security apparel, the need to protect has always been an established market. Armoury which is heavy and cumbersome, difficult to move in have now become sheets of synthetic fabrics threaded into one another. As the industry develops and the materials to choose from become plentiful, there is an active choice in adapting the history of uniform in order for the new designs to be better advanced. The construction of uniform and the way it has changed is also a good indicator as to how warfare has changed, how weapons are manufactured in order to get past the materials and into the body.

Whilst weapons maintain greater impact and power, the uniform has a chance at stabilising blood loss and potential injuries. The tightening of webbing straps on open wounds, slings protecting the frame of the body when bones are broken and dabbing material onto skin to move away dirt and soak up moisture all play a part in protecting the body. While they may not be the most obvious signals, they remain an integral part to the operators relationship with the environment.

Like any industry, protective apparel has gone through relentless changes. Yet the core principle of protective apparel remains the same; to create a barrier between an incoming threat and the human body. The construction of protective garments profits from materials which have been tested for their strength and durability. Through these materials, designers create a constructed form which emulates the silhouette of the human body. As conflict remains and fear is rationalised, the market for these materials remain profitable.

Image (1&2) ©U.S. Naval Forces Central Command/U.S. Fifth Fleet

[1] Embodying the military: Uniforms by Sharon Peoples – Australian National University.

History – Developments of Protective Apparel

The development of body armour stems from the survival instincts to protect. Using material in order to do this has provided a practical use but it is also a symbolic gesture, one that visualises the incoming threats and the power of the combatant. Early manufactured body armour from Egypt (BC 3000 – 1200) used armour for its symbolic use, protecting those who had the rank and wealth to afford it. Scale armour which had small plates of bronze sewn into a padded backing were used at this time, long after wearing the armour for protection the scales would be found in tombs[1] and palaces[2], amplifying their position as a carrier of wealth and power. Whilst uniform has consistently played with the notion of hierarchy, the use of armour for armies was eventually delivered in the city of Sumer in Mesopotamia (BC 2500). Stele of the vultures depicts Eannutum, king of the city state of Lagash in battle with his army. The function of protecting the army is mirrored by the wealth of the uniform, a power which emulates the idea of a team spirit, one that rests on motive, skill and competition. In this sense, the uniform is an indicator of behaviour which is insular, motivated by its power and intelligence to succeed. The fascination lies on how this is visualised and adopted, both as materials develop and political operations change.

Value of those who could afford armour continued in different ways. Muscled cuirass (breastplates) were an advanced material for Roman soldiers between 100-200 AD[3] used by those who could afford it. The romans also used segmented plates known as Lorica Segmentata[4] which created a formality to the uniform, constructed together as metal strips which were bent to fit the body and fitted together by straps and buckles. Visually, the armour creates a constructed form which wraps around the body to form a tight, compact unit. The weight of the metal causes restriction, through this restriction the material is both positively safeguarding the occupier from attack while adding weight to his frame which could affect performance. In order to move from this restriction, training exercises which use the weight of the armour are important in maintaining performance levels.

In this sense, the armour adjusts the behavior of the combatant, actively loading the weight on his frame to feel strong, confident and conscious of the threats which are in front of him and the comfort for which the armour may bring if hits do occur. As a collective, these materials are interesting for their behavior, their design in building a language to which attacks can be avoided.

Image (1) ©U.S. Naval Forces Central Command/U.S. Fifth Fleet

[1] Body Armor: Page 12 – ‘Tutankhamun’s tomb also provided a close-fitting sleeveless cuirass made from thick tinted leather scales sewn to a lining.’

[2] Body Armor: Page 12 – ‘palace of Amenhotep III, Thebes of BC 1430.’

[3] Body Armour: Page 36 – Romans also made use of the muscled cuirass (breastplate) modelled on the torso. Originally it was used only by wealthy soldiers.

[4] Image:fotolibra.com/gallery/1194731/lorica-segmentata-segmented-plates-roman-armour/

Industry – Engineering Uniform

Below are a series of short introductions which focus on leading inventors of synthetic fabrics which come to inform this section of the website.

Nylon

Wallace Carothers (April 27, 1896 – April 29, 1937)

Whilst the effort made in profiting from the manufacture of Nylon is separated and drawn together through the combined efforts of employees, the originating creation points to academic turned inventor Wallace Hume Carothers. With a grasp of chemical literature and a breadth of experience formed by obtaining his degrees at both Tokio College and University of Illinois, Carothers was indicative of pursuing academia with scope for consistent progression. Developing from his academic practice Carothers became a chemistry instructor at Harvard University and then later in 1927 he accepted a place at Du Pont, focusing his attention on analysing polymers, a field that hadn’t been fully explored in the U.S. at the time.

Carothers work at Du Pont focused on proving the existence of macro-molecules by building them from scratch. His focus informed his process ‘The idea would be to build up some very large molecules by simple and definite reactions in such a way that there could be no doubt as to their structures.’ His reasoning was based on German chemist Hermann Staudingler, who had previously proposed that polymers were actually made of macro molecules held together by ordinary molecular bonds. After researching, Carothers presented his ideas in articles for the Journal of the American Chemical Society and Chemical Reviews, both layering the basis for much of Modern Polymer Science.

The ambition in his ideas were shared with his team, using ideas circulated from Carothers research, assistant Arnold Collins created a synthetic rubber in 1930 formally known as Polychloroprene. In addition, the teams focus on trying to make large molecules a reality, was adapted by preparing esters which had a molecular weight between 4,000 to 6,000. In order to increase the molecular weight, Carothers used a molecular still to remove water which were visible in the later stages of reaction. Working with the technique, Carothers assistant, Julian Hill found that the molecular weight could reach more than 12,000. The success of the ester proved to be Du Pont’s most promising synthetic fibre but in its early stages the fibre was water soluble and melted at low temperatures. In order to progress, the material had to adapt to become marketable.

In 1934 Carothers analysed his research and concluded that rather than using esters, it would be better to build polyamides, chains of amides, or proteins. Experimenting with different combinations of chemicals his team began to formalise plans. Success came as the team had identified their first polyamide, a synthetic polymer which would be formally known as Nylon. For the success of it all Carothers didn’t rationalise the rewards, instead he suffered with his mental health, a depression which ultimately killed him.

Du Pont continued to develop Nylon, creating billions of dollars of profit which have continued to have lasting financial strength. A key market player, by 1941 Nylon proved its power as it became 30% of the hosiery market and developed into products for military needs. The influence of synthetic fabrics continues to adapt to the market. Nylon provides an understanding for academics and scientists to learn from long after its creation, continuing to be a viable material which forms part of the materials we use in everyday life.

Kevlar

Stephanie Kwolek (July 31, 1923 – June 18, 2014)

After graduating from Margaret Morrison Carengie College with a Bachelors Degree in Chemistry and presenting her work at the University of Pittsburgh, Stephanie Kwolek worked as part of the Pioneering Research Laboratory Team at Du Pont conglomerate industry in 1948. The group, set up soon after the creation of Nylon, presented Stephanie with a chance to research and experiment with new materials whilst keeping to the policy and procedures set by supervisors.

In 1965 a brief was sent out to Du Pont employees to find the next high performance fibre that could replace the steel wire in tyres. Stephanie reacted by working with long chain polymers and found a solution which was peculiar in its nature, a thin, watery and opalescent solution. Through the use of spinning, the polymer solution was turned into a fibre and the outcome had characteristics which were strong and stiff. The material was light and strong, strong enough to be five times stronger than steel. The result was Kevlar, a material which would come to represent a key ingredient within the defence industry.

The strength of Kevlar is estimated to be around 3260 MPa (unit of measure used to quantify internal pressure and stress. It is defined as one newton per square metre) and a relative density of 1.44. The strength is formed through the inter-chain bonds, these intermolecular hydrogen bonds form between the carbonyl groups and NH centres. Additional strength comes through the aromatic stacking interactions between adjacent strands and its relatively rigid molecules which tend to form mostly planar sheet-like structures.

The success of Kevlar both commercially and creatively has grown to be a versatile material which adapts to different uses and markets. Famed for its use in combat environments, the material is also attributed to sportswear, audio equipment, home appliances and the building industry. Its versatility as well as its strength continues to re-evaluate its place within the market, whilst consistently rendering the bodies shape in order to secure and protect it whilst in operation.

Nomex

Wilfred Sweeny (1926-2011)

Developments made at Du Pont by Paul Morgan and Stephanie Kwolek along with the research made by Wilfred Sweeny informed the creation of Nomex, a flame retardant fabric produced in 1967. Sweeny found a way to make a molecular-weight product that could be spun into a tough crystallisable fibre which possessed thermal and flame resistant properties.

The fibre absorbs heat, keeping it away from the wearer. The fibre also swells and thickens when exposed to heat, increasing the protective barrier between the heat source and the skin. After the fibre has completely cooled down and is taken out of the heat, the garment may crack or break open, showing that the fibre has done its job, absorbed the heat and has carbonised, providing extra seconds of protection without impairing mobility.

In addition to its use in protective apparel, Nomex brand paper has been providing high-performance electrical insulation for motors and generators. The electrical and thermal properties help to extend the life of electrical equipment as well as reduce premature failures and repairs. Nomex can also be found in consumer appliances, industrial equipment and transportation equipment such as high speed trains

Image (1) ©U.S. Naval Forces Central Command/U.S. Fifth Fleet

SUIT / FUEL / BERGEN

Three publications I created in 2015. Click on the image to view a PDF copy of the publications.

Suit – A series of interviews with soldiers turned artists, soldiers turned journalists and artists working in zones of conflict.

Fuel – A series of interviews with contemporary artists exploring themes of conflict, loss and technology.

Military Textiles: Bergen – A photographic essay exploring the role Military Apparel plays in environments of conflict.

Birth

The need for comfort is recognised from conception as a need for protection and warmth; sustaining momentum through pregnancy and built upon after birth. The intimacy of comfort and the pleasure it releases is a chance to rationalise and ease the thoughts of the mind, both for mother and child.

Cognition is the mental action of processing knowledge and understanding it through thought, experience and the senses. The instinct to protect and provide comfort is built through pregnancy as the delicacy of movement and the caution in taking on an active role is rationalised, thought over and managed before taking place. The memory of pregnancy and the reality of carrying life over a duration of nine months is developed when the child is born. The child, protected by layers of fabric, is kept warm by the mother’s action to secure and protect the body of the child. The comfort of a blanket, the security of folding and tucking the child into a compact unit, illustrates the narrative between protection in pregnancy and protection in birth. Fabric embodies our comfort and presents itself throughout our lives in the beds we sleep in, the layers of clothes we wear and the tents and shelters we use in the natural landscape. As a reality, it is functional and pragmatic, but as a theory I am arguing that the use of fabric is an extension of the relation between mother and child, which in practice is one of the first key indicators of security in our reality.

Security

Security is being free from danger and threat. The barriers which are created to avoid such jeopardy requires the man hours to put thought into action. Building borders, firing weapons and strategizing a movement of attack form parts of securing a community. These physical components run alongside fear. It is through the physical properties of security and the mental edge of fear that industry moves forward, pushing the breath of the adrenalized man, the finance of the forces and the logistics of the designed weaponry into territories of conflict. The reality resting in the open-aired battlefield is felt by the armed operative alone, but the history, business and growth of action resides in the people involved in the process of getting them there in the first place. In this sense, the collective energy is found in the logistics of transportation, the recruitment of finding the required minds and the products bought to support the needs of the combatant.

The machinery adds fire to the environment and the uniform creates security; a base stitched together to form a silhouette which follows the lines of the human body. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) addresses hazards including physical, electrical, heat, chemicals, biohazards and airborne matter. This method of designing requires design that incorporates testing, adapting and reviewing the advancements of technical textiles. It also requires a personal relationship with how the body will use and move in the material, something that can only truly be tested when the occupier of the uniform is in action.

Shells

Shells, explosive artillery projectiles creating damage. An environment torn apart, a route ruined, a shelter destroyed. These designed objects embed themselves into the landscape, creating appeal through their destructive properties. A shared instrument, the shell is a marker of power, stimulated by those who surround themselves galvanising at its presence.

The shells of soldiers are layered through the durability of the fabrics which coat their frame. The material carries the weight of the body and offers thermal insulation and freedom of movement while in the heightened environment. In this context, the shell keeps the body warm, retains malleable elasticity and camouflages the flesh from exposure. The uniform also carries the tools of the soldier, stitched together to hold the physical weight of the operation. The use of camouflage loses the soldiers visibility within the environment, and the weight of the uniform carries itself on the stress and strength of the soldier alone.

The disruption of the landscape is carried both by the fire of artillery projectiles and the veil of the uniform. Each coat the environment with different expectations; covering the body to be observant and present or shattering the body to the ground.